Project 1- Isaac’s Eye

After receiving confirmation of my employment at American University in Cairo (AUC) in early June 2017, I immediately began working with Frank Bradley, the director of Isaac’s Eye by Lucas Hnath. We began Skype meetings to discuss the play, but also to inform me about the space and procedures of a place that I’d never been. From the information given by the director, along with photos and PDF draftings of the theater (Gerhart Theatre), I began to compose my thoughts for the design. The story is a fictional account of Isaac Newton and his interaction with Robert Hooke, specifically centered around one experiment where Isaac inserted a needle into his eye socket to bend the eye and test a theory about optics. The theater is a small 90-110 seat black box with a re-configurable seating arrangement and typically a smaller budget for the productions.

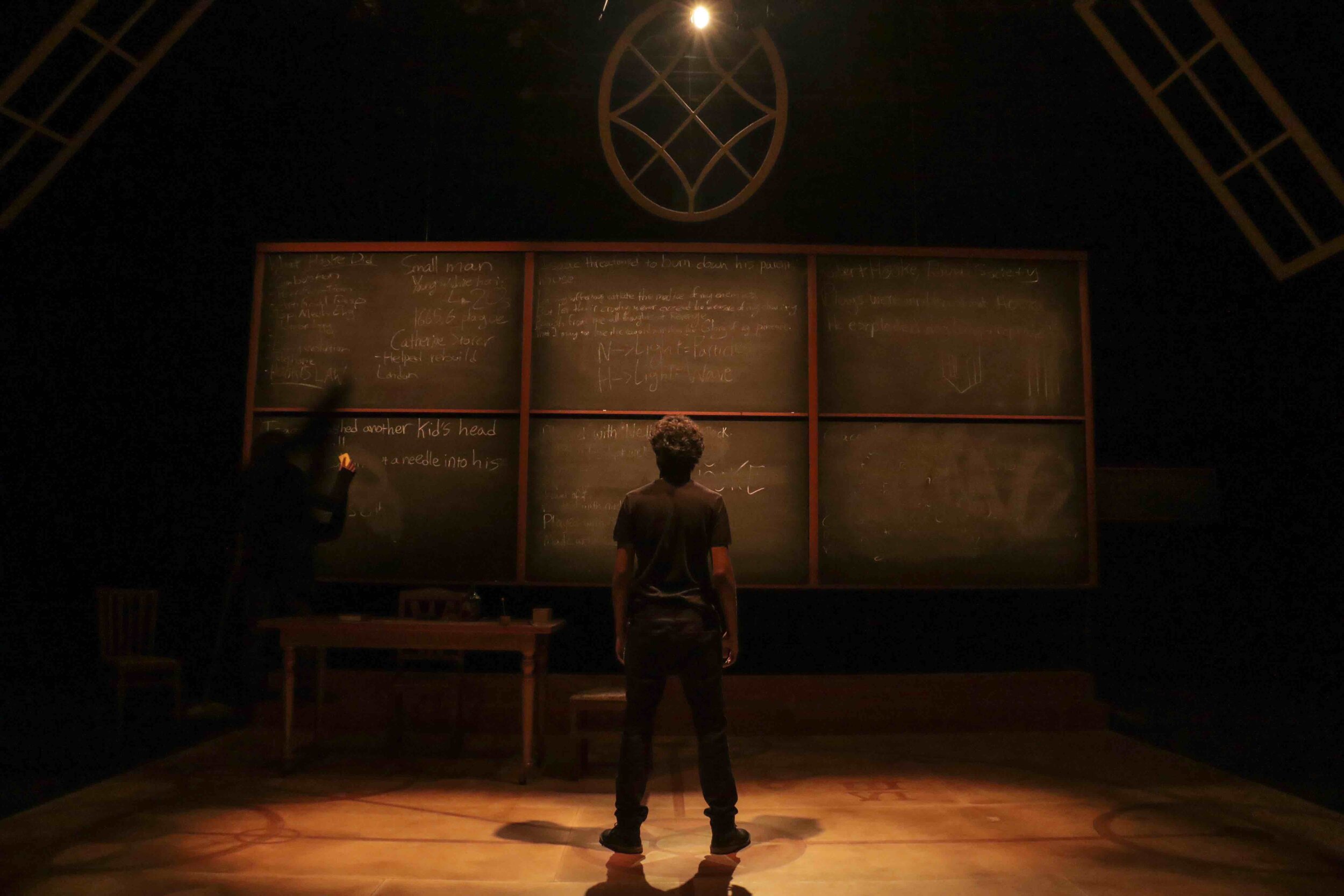

With all these factors in mind, I created a small thrust configuration with minimal scenery highlighted by a unique floor treatment. The floor, as the biggest scenic element, would be painted to look like a drawing of celestial arrangements by Sir Isaac Newton himself (a research drawing…he didn’t actually paint our floor). Using Vectorworks, a program that I have been unofficially married to since the 1990’s, I created a 3D version of the theater and the set. In late July I was able to send the director a “walkthrough” of the set and space with my initial ideas (https://youtu.be/TwEWk8mS97c). This was followed up with more Skype meetings where I could screenshare and make changes in the Vectorworks file live to improve our design choices. The main revisions were to diminish the presence of the windows, increase the presence and use of the blackboard, and to make the floor image look more “weathered.”

After a brief pause from designing while I packed up my entire life and relocated to the other side of the world, I resumed the Skype conferences with the director while he was still in the US. The ideas for the set were refined down to a simple table, two chairs, the large upstage blackboard (which had sliding panels almost like a jig-saw puzzle) and the painted floor. This led to another virtual walkthrough video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6y1NMmubn4), and even a .dae file that the director could manipulate the view of the 3D virtual space however he wanted. While we were unsure of some specifics, we agreed that the design could start to be built.

Working with the technical director was a learning experience for me in a new language (literally) of how to build and install the scenery. The following are the initial drawings from the Vectorworks file that were given to the scene shop.

Isaac’s Eye- ground plan

Isaac’s Eye- set details

Isaac’s Eye- paint details

While not at my normal level of detail and specifics (notice the lack of placement dimensions on the ground plan), I realized I had to leave myself open to a more flexible approach to the build and installation. Although I couldn’t be as precise initially, the level of craftsmanship provided by the AUC carpenters was some of the best that I’d ever seen. So I compromised some parts of the process to be reassured that others would exceed expectations. More specific drawings were provided to the staff based on their working styles, and I could even sit with them and redraft some elements to include their input. My assistant could also work directly with them using his copy of the Vectorworks file and the paint elevations to come up with better solutions. The amazing function of the large upstage blackboard, for example, would not have been as good without their problem solving ability. And the floor painting process was refined when a bucket of water (which may or may not have been put in the wrong place by me) was accidentally spilled onto the base coat and created a better weathered effect than the method I advised.

As the set was being built, the benefits of the 3D world created in Vectorworks began to really pay off for the addition of the lighting ideas. I’ve worked very diligently over the past decade to use this program to help communicate lighting ideas to directors in a somewhat new approach. Well…it was new 10 years ago, but fairly common now. But I would like to think that the work that I’ve put into this specific use to accurately communicate lighting ideas still makes it unique. Before the light plot was finalized I showed the director a PowerPoint presentation (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XWWjHpNKFU) of the lighting systems to make sure we were “seeing” the same thing. The first part of the video of this presentation is from an earlier stage of the set with simple reference human figures (actually Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke) and shows the basic systems and a few lighting ideas that we had discussed in our meetings. Using Vectorworks’ precision with photometrics I can place the lights in their actual place in the 3D virtual world, color and focus them. Not only does this allow me to show the director an accurate representation of the lights, it helps me catch any mistakes prior to the hang and focus. The second part of the presentation/video shows the final version of the set and the costume designer’s renderings for the characters. I take the time to do this so the director sees as closely as possible the idea of what our specific production will look like. In this section I can storyboard the progression of the play so my intentions for the cues can be discussed. After this presentation the director was able to give me notes on some of the cues several days before the lights were actually focused.

The following is the light plot. It is an excessive amount of lights. Due to a misunderstanding on my part through my poor comprehension of Arabic, I thought the lights were placed differently on the catwalks (shown in red). In reality they were placed slightly higher. This one meter difference meant that the degree designation was incorrect and there were more lighting units used than necessary. The plot was hung on a day that I was teaching, so this mistake wasn’t caught until after the work was finished. Rather than change everything, I was able to adapt my focus and cueing. The good thing that came from this was that even when presented with a plot that had more lights than any other production in that space, the staff never hesitated. When I admitted my mistake they were more than willing to re-hang everything, but it was decided the time and energy would be better placed elsewhere. One must know which battles to fight.

Isaac’s Eye- Light plot

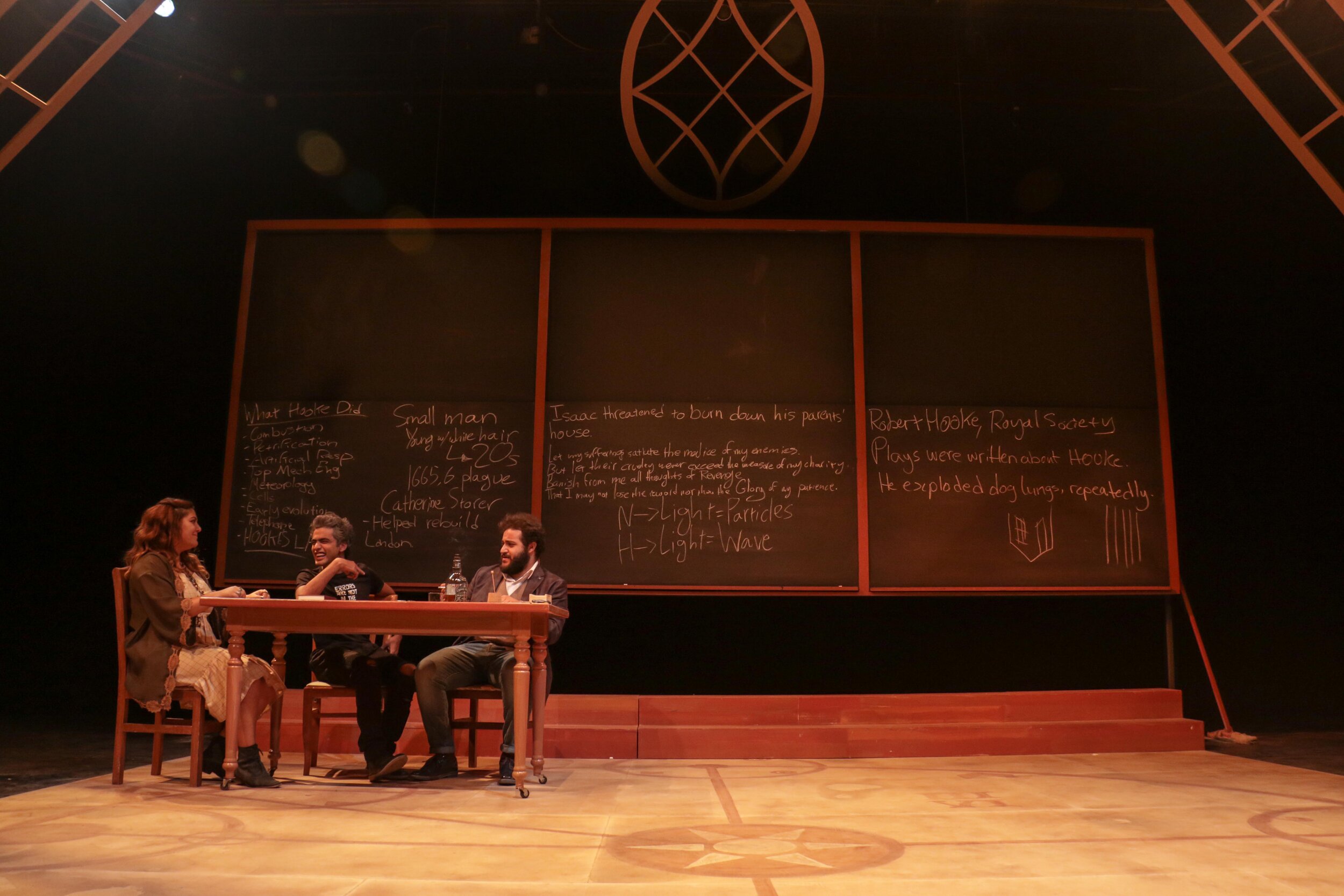

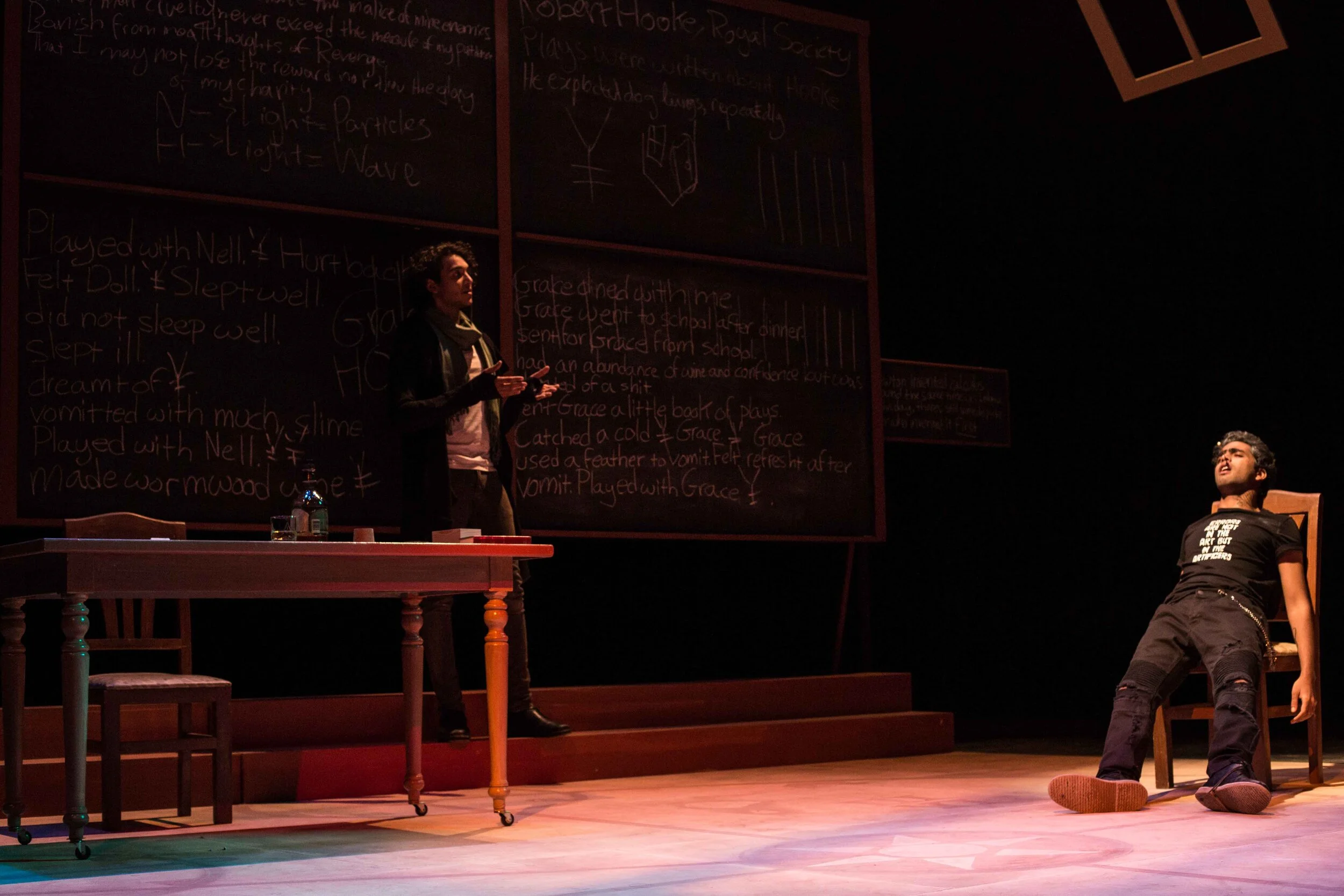

Despite my learning curve in the new situation, the tech process went remarkably smoothly. Because of the clear communication of our intentions through the storyboards, the director and I were able to tech the play in around four hours. This left the remainder of the rehearsals prior to dress rehearsals for the actors to do run throughs. By the time the play opened, it was in the best shape it could possibly be and was one of the better performances I’ve ever seen at the college level. Below are some images from the final dress rehearsal.